Independence Day this year felt like half the country declared independence from the other half. As if we were on opposing sides of the street for the annual neighborhood parade, both dressed in red, white and blue, each waving American flags but cheering for different beliefs about the same country.

This is not new in our history. We have had arguments about the meaning of America since the beginning of America. Disagreements have often focused on the question of what role the government should play by either defaulting to culture or shaping it.

The Civil War was provoked by a Southern culture rooted in white supremacy and featuring the enslavement of people of African descent. Southern preachers defended this as a moral vision of a Christian nation. Not all white abolitionists in the North believed in complete equality, but they felt a religious and moral duty to oppose slavery. Southerners believed the federal government was promoting unbiblical ideas about equality and using the Constitution as a legal cudgel against a natural way of life that history and tradition confirmed.

Advances in human and civil rights for Black Americans, women, and LGBTQ citizens were finally written into law; unfortunately they were never written on the hearts of those who resented the strong arm of government to enforce those laws and force their compliance. Similarly, while our country is, at its core, a nation of immigrants, resistance to those who are felt to be “other” to white Protestant Christians has perpetually dimmed the beacon of freedom we have sought to beam to the world. Ultimately our elected officials are charged with the daunting task of holding a diverse nation together in the face of our varied histories and cultures. At its best, law and policy come out of a process of listening to and learning from different understandings of “E Pluribus Unum.” Negating our country’s diversity has always been a recipe for conflict and violence.

We are living through another of these moments of reaction to the use of government to promote “a more perfect union.” We are seeing the dismantling of our democratic institutions and the mass reduction of federal employees who have stood sentinel on legal protections of vulnerable groups, the environment, health, and workers. The so-called “administrative state” is viewed as the enemy of those who want freedom from social, religious, and economic interference by the government. There is little doubt that the consequence of this reaction will be harmful to the common good or that those least capable of helping themselves will be most affected.

Why does this feel different than at other times in our history?

Nearly 40 years ago, a conservative resurgence began among Southern Baptists who believed that the leadership of the Convention was forcing a liberal agenda on them. For a decade or so, they organized politically to take over the apparatus of the denomination. Many who were alarmed by their success were too late in responding, believing that this was just a swing of the pendulum and things would eventually balance again. What was different this time, however, was that the winners nailed the pendulum to the wall. They completely controlled all the institutions and left no room for dissent.

This is where we are today. All three branches of government have removed guardrails to Executive power, unleashing our worst impulses on the powerless. Suppressed voting rights and access, gerrymandered districts that artificially create party homogeneity (effectively segregating Democrats and Republicans), and politicized legal systems that defend a takeover of one part of our nation over another conspire to keep us from seeing those patriots across the street as fellow citizens.

So, what do people of faith do in the face of this?

First, we remember that history is full of surprises. My pastor, Rev. Dr. Timothy Peoples, quoted the historian Howard Zinn in his sermon on Independence Day Weekend: “There is a tendency to think that what we see in the present moment will continue. We forget how often we have been astonished by the sudden crumbling of institutions, by extraordinary changes in people’s thoughts, by unexpected eruptions of rebellion against tyrannies, by the quick collapse of systems of power that seemed invincible”1

Our faith traditions are full of stories of turns toward justice inexplicable apart from the partnership of divine initiative and human cooperation. Each time a surprise arises, something new is born. What has been undone can be redone, but what comes next must be more than replacing what is with what was, lest we learn nothing from history and perpetuate a cycle rather than breaking it.

We need a person-centered politics today that is rooted in human dignity and a sense of community – one that transcends individualism and tribalism. We have to love our country more than our party and our neighbor’s wellbeing more than our personal prosperity. When our team becomes more important to us than the game, we all lose.

Defeating divisive politics will require us to view people on the other side of the street as opponents, not enemies. Mending the frayed social safety net and the fraying social fabric means refusing to practice a politics of resentment, no matter how satisfying that may feel at the moment.

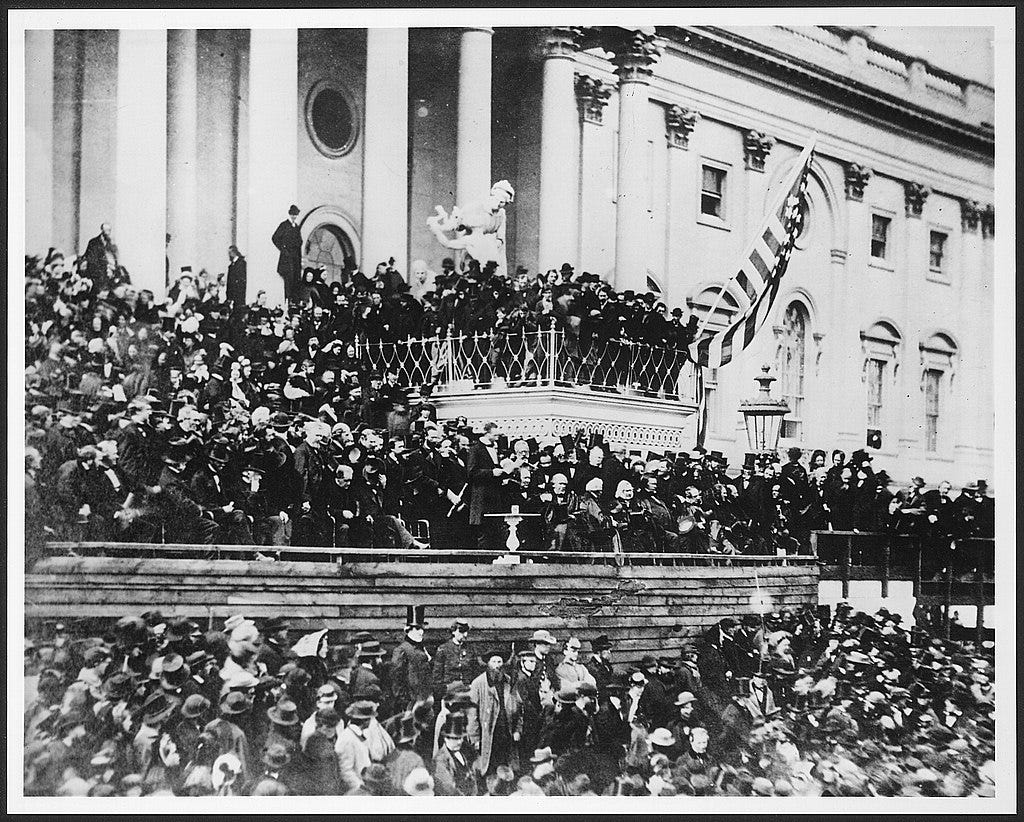

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address was delivered as the Civil War was winding down. It sums up the spirit that will help us heal in the aftermath of this uncivil time. He concluded by saying: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds . . . .”

Finally, we must not give up. It is the nature of faith to live in hope – hope for a future promised but not yet seen. Faith includes both a vision of a just peace that prevails for all and the courage to persevere in spite of moments when that vision seems eternally elusive.

Saint Paul exhorted Christians in Galatia to steadfastness in the face of discouragement. His counsel is ever-timely for all people of goodwill: “And let us not be weary in well doing: for in due season we shall reap, if we faint not” (Gal 6:9).

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2003), Afterword.