This post is open for comments. Build a conversation around your concerns. Encourage one another. Be Christ’s light in the surrounding darkness.

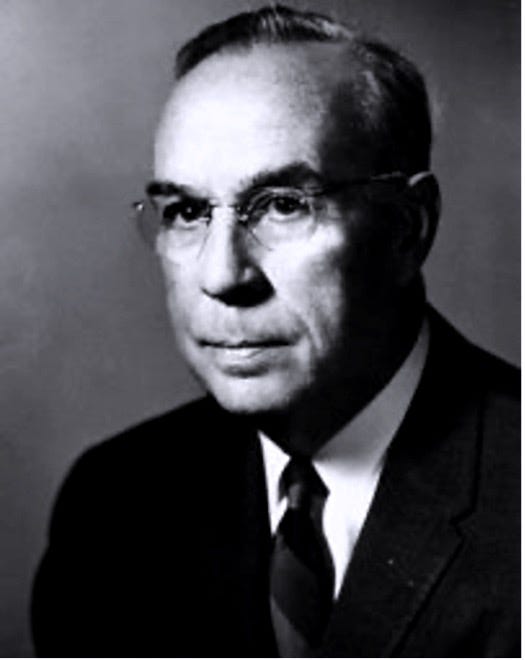

George Arthur Buttrick, the British-born-and-educated senior pastor of New York City’s Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church (1927–1954), and “Preacher to the University” and pastor of Harvard’s Memorial Church (1954–1960), was one of the most sought-after and frequently quoted English-speaking preachers of the 20th century.

His thirteen books, including the best-seller Prayer (1942), as well as his general editorship of the twelve-volume Interpreter’s Bible (1951–1957) and the five-volume Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (1962, 1976), made him a familiar household name.

As a lifelong pacifist, and conscientious objector during World War I, Buttrick served as a YMCA chaplain’s assistant assigned to a British regiment in the European theater for a mere ten days, until he fell wounded.

Several decades later his secretary wrote in her diary: “He said in the first war he had a throat affliction which caused the Doctor to say ‘You’ll never preach.’ It was a pretty hard pill to swallow—but out of it he learned that God’s will is sovereign—and first thing he knew after that he was preaching.”1

Those words—“God’s will is sovereign”—are worth taking to heart in moments of deep darkness and despair, and not least when chaos reigns and all hell breaks loose.

On September 8, 1939, while serving a two-year term as president of the Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America, Buttrick addressed the nation via NBC radio, exactly one week after Germany’s invasion of Poland, which marked the onset of World War II.

In his radio address Buttrick remarked:

Our American Protestantism will do well to strengthen our government’s purpose to keep us out of war. But our motives must be clear. It is very easy to be neutral from base motives. We must be neutral from high and costly motives: not for physical safety, not in the attempt to maintain an impossible isolation from world problems, assuredly not for commercial gain, but rather because we know war is futile and because we are eager through reconciliation to build a kindlier world. Let us remind ourselves constantly that war has been proved futile. Twenty-five years ago we tried by means of war to “make the world safe for democracy.” Now the world tries once more to cure hate by means of hate, to mend killing by multiplied killing. Twenty-five years hence our children may be fighting against other coercions, bred of the hatreds and poverties of war, different only in name from present coercions, unless a worthier spirit and a nobler planning enter world affairs.2

Buttrick cited five actions for American Protestantism to take: (1) “Keep unbroken our worldwide Christian fellowship,” (2) “Lead the nation to repent, forbear, forgive, and in every word and work of reconciliation,” (3) “Enter into the fellowship of suffering with the millions on both sides of every battle line,” (4) “Strengthen our government’s purpose to keep us out of war,” and (5) “We can pray.”

He concluded by saying:

True prayer is not a last resort. It is not an escape. It is not a plea for security. It is a beseeching that God’s compassionate will may be done . . . . It is a spiritual force stronger than all armies. It is a healing serum injected into the one body of mankind of which all nations are members and of which Christ is the Head. Quietly it overcomes areas of dark infection and disease. It is the antidote of hate and the overcoming of violence. Our worship during these critical times should acknowledge the kinship of all nations; our churches should be filled with the Spirit of earnest and unremitting intercession. This is the nobler energy for lack of which the world is arid and torn. Let us pray and pray again in home, in business, in church; and let us then strive to live more nearly as we pray. Thus, “may the God of peace lead us into all peace.”3

Believing that Jesus Christ never calls his Church to advocate and promote war, but rather to be non-violent makers of peace, George Buttrick took that sacred charge of Christ seriously.

On December 27, 1940, Buttrick accompanied Rabbi Cyrus Adler, president of New York’s Jewish Theological Seminary, on a “peace visit” to President Franklin Roosevelt in the White House. The purpose was to avert the outbreak of war in Asia with a proposal that the President commission a U.S. peace delegation to Japan—an initiative that, lamentably, Roosevelt rejected.

One year later, on the evening of December 31, 1941, two weeks after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and twenty days after the U.S. declared war on Germany and Italy, Buttrick addressed his Madison Avenue congregation during its Watch Night service as the nation braced for the uncertain danger and human cost of being at war on two broad fronts.

Now, in mid-2025, the United States of America is once again entangled in foreign land wars, this time on the three fronts of Ukraine, Gaza, and Iran, not to mention the invisible technological combat taking place daily in global cyberspace, of which the immediate and long-term consequences remain unknown.

We American Christians simply do not know what may yet be required of us in being faithful to Christ and the gospel at such a time as this, compounded by the duress of an increasingly autocratic and inhumane regime extending its draconian reach throughout the country by plaguing the nation with a war against itself.

Perhaps then George Buttrick’s words, like those of any good captain aboard a battered ship during a frightful storm at sea, might confirm in us an unfailing trust in the only wise, just, ever-loving, and everlasting God who remains sovereign in all human affairs. For regardless of what may transpire during any and all of our tomorrows, the past, the present, and the future belong to the saving grace of the one holy God.

Just so, we turn to George Buttrick’s Watch Night address, that his incisive mind and pastoral heart may speak now to us.

GEORGE ARTHUR BUTTRICK — WATCH NIGHT, DECEMBER 31, 1941

The customary word tonight, however true, would be almost an affront. We cannot think tonight primarily about the swiftness of our days or even about New Year resolves. This Watch Night is not customary. No generation save ours has seen two mammoth wars. On no other Watch Night was a whole planet under arms.

No, I shall not speak to you now about the war. It is there—the undertone of all our thoughts. We could not, and should not, forget it. Yet the Church should not discuss it except to lift us above it. So I speak to you tonight about your day-by-day life during 1942.

Make the necessary sacrifices, and accept the necessary changes. Then live as normally as times permit. Our aim in the war is reasonable freedom to live a normal life—to work honorably, to make a home, to deepen and irradiate the spirit by fine books and music, to rejoice in friendship, and privately and corporately to worship God in the Face of Christ. Then let us keep life normal insofar as abnormal times allow: we must not needlessly surrender the very boon for which we strive. Do the daily job—unless the tragedy of mankind undeniably calls you to some unwonted service. Keep the glow of home. Deepen the spirit of true culture: the Viennese orchestra leader was right who said, “If we must perish, let us perish to the strains of great music.” Cleave to your friendships, and give some time to simple pleasures: your soul is like a fine watch-spring, and cannot always be wound tight. Above all, keep Christ in your thoughts both by private devotion and corporate prayer. If He is forgotten, any victory is defeat. So make the necessary sacrifices cheerfully, and accept the inevitable changes cheerfully. Then live as quietly and normally as times permit.

II

Keep a steadfastly Christian mind. You will be wise not to spend too much time on the newspapers or at the radio. A briefer (rather than longer) survey of each day’s news in the public press, and a listening once (not too late at night) to the radio news is enough in wisdom. The commentators have not been notable for foresight, and those who profess to have secret information are a minor menace. Do not give way to hatred. The people of Germany and Japan are not blameless: they are more susceptible than they should be to the indoctrinations of war. But they are not essentially different from ourselves. When left alone by demagogues and firebrands, when free from the carking poverty which makes war seem almost a release, they wish like all [others] to work and play, love and worship.

Do not give way to frenzy. In regard to air raids, which are quite unlikely but still possible, know what you should do and be ready to do it; and then go your steady and customary way. Beware of racial prejudice. As you wish people to honor your conscience, honor theirs, especially if it be different from your own. Resist all rumor-mongering, and be patient. If these counsels are to be heeded, prayer is indispensable. Keep time for prayer—a brief time after breakfast in the morning, moments now and then during the day when you think about God, and a longer time at night. Nothing should intervene between your nightly prayers and your sleep. Then, during sleep, your subconscious mind will continue in that saving climate which your last waking thought invited. Public prayer is as requisite as private prayer, for by nature we are members one of another. So pray, keep the fellowship of the Church; and let your prayers save you from vindictiveness and all distorting passion.

III

Another word must be spoken. Statesmen are all discussing and promising a new world after the war. That fact is one of the reassuring signs. But what statesmen do not tell us (perhaps because it is not their main responsibility) is that there can be no new world without new people. Plans are desirable now for a just and durable peace. But unworthy people can defeat the worthiest plans. The ancients Greeks tried to make a corpse stand upright: it had hands, eyes, feet, a complete body, but it would not stand. They finally reached the conclusion that there was something lacking inside. The lack of something inside is one for which nothing outside can ever atone. We know there must be new people. But we cannot say it unless we ourselves are willing to become new. I cannot say it to you unless I am willing to become new. And the new life is the gift of God. This Watch Night service requires of us a new surrender to God—a complete surrender and a complete consecration.

So make that resolve and commitment now, tonight. Not this and this resolution for a year: the resolutions are best made morning by morning and night by night. Then, if they are broken, they can be renewed when God in His mercy gives a new day. This new consecration is not merely some “new year’s resolution,” but a complete surrender—with no eye on the clock, and with no trust whatever in our own strength. We must give ourselves here and now once more outright to God. Then, and only then, new life will spread from us, by contagion, through the earth.

IV

It may be that God will grant us peace before another Watch Night service. We do not know. It is wise not to guess. We must live the days, a day at a time, as He gives them. But it is human and proper to pray. We shall be loyal to one another in firmest friendship in this Church, because we shall be one in prayer and in the faith of Christ. As this year dies, He lives. As the new year is born, He is born again. On the darkest day the sun shines as brightly as ever above the clouds. On the darkest night the sun has not turned from us, but only we from the sun; and as we turn again the morning greets us. We ministers promise you, so far as we have grace and power, that Sunday by Sunday, you shall rise above the cloud and see the sun. Then, as you go back to a shadowed earth, you will yet know that Christ lives and reigns. You will have strength to walk and endure, to watch and wait, to trust whatever sorrows and changes come, until God in His mercy breaks the cloud and gives clear shining after storm.4

This post is open for comments. Build a conversation around your concerns. Encourage one another. Be Christ’s light in the surrounding darkness.

1 Elizabeth Stouffer Diaries: 1932–2007, Sunday, March 4, 1945 (Cambridge, MA: Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University).

2 George Arthur Buttrick, “A Statement Concerning American Protestantism and the European War,” Broadcast over the facilities of the National Broadcasting Company on Friday, September 8, 1939, The Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church News, George Arthur Buttrick Papers, HUG FP 90.42, Box 16, Sermons (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Archives, Copyright 1939), with permission of David G. Buttrick.

3 Buttrick, “A Statement Concerning American Protestantism and the European War.”

4 George Arthur Buttrick, “Watch Night Address,” George Arthur Buttrick Papers, HUG FP 90.42, Box 7, Sermons, M.A. 1057 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Archives, Copyright 1941), with permission of David G. Buttrick.